Apr 16, 2025 By: Lorraine Sim

Volume 9, Cycle 3

https://doi.org/10.26597/mod.0320

Can modernism be happy? Or perhaps the question should be: can modernist studies be happy? These questions started to preoccupy me some time ago when I was seven weeks into teaching my undergraduate course in modernist literature at Western Sydney University. As we were about to turn our attention to Jean Rhys’s novel Voyage in the Dark (1934), I felt compelled to apologize to my students. I was asking them to delve into yet another textual universe of trauma, alienation, and unease. The only somewhat playful relief on offer that semester was Un Chien Andalou (1929)—hardly a set piece for eudaimonia. I assured my students that modernism was not all doom and gloom: modernists had fun, they could throw a good party. At the conclusion of the course, I routinely show archival footage of people dancing the Charleston to demonstrate just how much fun modernism can be. But in all seriousness, this experience prompted me to start thinking about the question of modernism and happiness, and why it has remained such a conspicuously absent topic in modernist studies both past and present.

As Sara Ahmed observed in her 2010 study, The Promise of Happiness, we are in the midst of a “happiness turn.”[1] Happiness, wellness and wellbeing are large, lucrative culture industries. This is exemplified by the large number of books, podcasts, seminars, and websites dedicated to informing us what happiness is and how we can attain it.[2] If we follow Darrin McMahon’s comprehensive intellectual history of the idea, we are possibly in the biggest happiness craze since the eighteenth century.[3] In recent years several governments, such as New Zealand’s, have focused more attention on issues of individual and social well being.[4] In 2018, Tracey Crouch was appointed the unenviable task of serving as the UK’s first Minister for Loneliness, a role which clearly aligns with issues of community and wellbeing. By contrast, some commentators fear that happiness and wellbeing have become instruments of neoliberalism as much as capitalist enterprise.[5] As John Updike quipped, “America is a vast conspiracy to make you happy.”[6] In academia, Happiness Studies is an established interdisciplinary field, and an increasing amount of scholarly and empirical research on the topic is being published in disciplines across the Social Sciences and Humanities.

While we witness a popular, political, and scholarly “turn” towards happiness, modernist studies has remained largely silent on the subject. Only a few articles and book chapters on the topic have been published, predominantly in relation to specific writers or designers.[7] Other studies have engaged with happiness and wellbeing in tangential ways; for example, in relation to utopian politics and philosophies of the period.[8] At the present time, there is no in-depth account of ideas or the aesthetics of happiness in modernist literature, art and culture. This is a remarkable oversight given that happiness has functioned as an “overarching aspiration” since “the ancient world of classical Greece” (McMahon, Happiness, xiv). Providing an account of what happiness might mean for modernism is a task that exceeds the scope of this essay, and one I reserve for the larger project of which this essay is a part. Rather, this essay investigates possible reasons why the field has occluded happiness from its critical narratives, and some of its implications. In particular, I focus on the changing fate of happiness in the history of philosophy and the effects of a privileging of negativity in modernist studies and critical theory. My discussion goes on to provide a range of examples of happy modernisms in literature and the visual arts. These analyses are by no means exhaustive: they are offered as a set of critical starting points that exemplify the many and varied ways in which happiness, as an idea and theme, is present in modernist literature and culture. To engage an Australian idiom, it is, I propose, a “furphy” that modernism is inherently unhappy.[9] It is rather modernist studies that has insistently told us so.

Modernism, Modernity, and Happiness

In spite of the many revisionary approaches that have transformed modernist studies in the past twenty-five years, modernism continues to be aligned with the negative, with trouble. This assessment of the modernist temper and worldview was succinctly illustrated in Douglas Mao’s keynote presentation at the 2019 “Troublesome Modernisms” conference in London. In his opening discussion of the relationship between “troubled” and “troubled by” as it pertains to modernist literature and literary scholarship, Mao recalled the common objection made by critics from the mid-twentieth century regarding modernism’s “fetishizing of inner turmoil” and “investment in the negative.”[10] I was struck that this glancing alignment of modernism with trouble/negativity/inner turmoil was accepted by the audience as uncontroversial—a self-evident truth. What was apparently more troubling and far less interesting to various delegates (if gossip overheard later in the pub counts as evidence), was my paper, presented later in the conference, on modernism’s interest in happiness.

Throughout its critical history, the modernist temper has been defined through a prism of negative moods and affects: trauma, anxiety, alienation, angst, unease, affront, incomprehensibility, and crisis. In the introduction to Bad Modernisms, Douglas Mao and Rebecca Walkowitz discuss a number of foundational accounts from the 1960s and 1970s by critics including Lionel Trilling and Irving Howe, all of which propose that modernism’s “bad manners were bound up with bad times, bad feelings, and a radical destabilizing of the criteria by which a work of art’s goodness or badness could be judged.”[11] Charting the mechanisms by which the institutionalization and domestication of modernism during the mid-twentieth century simultaneously rendered the badness of modernism, at least for a time, good (i.e. canonized, bourgeois, fashionable), a key aim of the volume was to reinvigorate thinking about modernism’s badness, and it includes several essays on bad feelings, self-negation, and other “fertile negatives.”[12]

In their influential 1976 essay, “The Name and Nature of Modernism,” Malcolm Bradbury and James McFarlane describe the “[c]ultural seismology” that bore early twentieth-century modernism as “cataclysmic.” The age was one defined by what they describe as an “apocalyptic, crisis-centred” view of history.[13] Early in the essay, by way of exemplification, they quote the British art critic Herbert Read on the current “revolution” in early twentieth-century European art: “[I]t is not so much a revolution, which implies a turning over, even a turning back, but rather a break-up, a devolution, some would say a dissolution. Its character is catastrophic.”[14] In 1999, in his introduction to The Cambridge Companion to Modernism, Michael Levenson echoes these familiar characterizations of a period marked by crisis and “forms of creative violence.”[15] “Crisis,” he writes, “is inevitably the central term of art in discussions of this turbulent cultural moment. Overused as it has been, it still glows with justification. . . . It is fair, and indeed important, to preserve memory of an alienation, an uncanny sense of moral bottomlessness, a political anxiety” (4, 5). Canonical works of Anglo-American and European modernism, such as Edvard Munch’s The Scream (1893), T. S. Eliot’s The Waste Land (1922), William Faulkner’s The Sound and the Fury (1929), Virginia Woolf’s The Waves (1931), and Pablo Picasso’s Guernica (1937), deftly exemplify these familiar moods of modernism.

The significant scholarly interest in recent decades in modernist affect, feeling and emotion has largely reinforced long-standing assumptions about modernism’s dominant moods. Shock, trauma, mourning and shame have, to date, received the most critical attention.[16] While scholars including Sianne Ngai and Allison Pease have drawn attention to the social and political significance of “minor and generally unprestigious feelings” as opposed to “grander passions like anger and fear,” the focus continues to be on the “aesthetics of negative emotions” such as “envy, anxiety, paranoia, irritation” and boredom.[17] While a critical turn to more positive affects and moods such as joy, hope and, indeed, happiness, has been more evident in recent years, the dominant critical narrative continues to centre on negativity and difficult or ugly feelings.[18] Recent scholarship on modernist humour has, likewise, emphasized the darker comedic forms of satire, irony and the absurd.[19] For many critics there is perhaps an unconscious assumption that to admit more affirmative or benign feelings into the critical conversation would be tantamount to a betrayal of the modernist project or experience, or a form of critical naivety. If some scholars have challenged claims regarding modernism’s rejection of sentiment and the sentimental, it is quite another thing for modernist scholarship to appear, well, soft.[20] Softness, like the sentimental, connotes weakness—all gendered terms. And, of course, the famous men of 1914 (Ezra Pound, Wyndham Lewis, T. S. Eliot) celebrated hardness and lack of sentiment in no uncertain terms.

In the wake of the many cataclysmic events and transformations that occurred in the early decades of the twentieth century—the First World War, the Russian Revolution, and the continuing violence of empire, to name only a few—writers, artists and cultural commentators of the period rightly responded to their historical moment with a sombre and critical eye, expressing a sense of ‘skepticism about the destiny of the species” (Levenson, “Introduction,” 6). However, I want to suggest that one of the reasons for modernist studies’ eschewal of happiness from its critical maps is because the field has consistently privileged narratives of modern experience centred on negativity and crisis, and canonized texts that in turn reinforce those narratives. If the new modernist studies has successfully challenged several of the “early histories of the epoch,” the history of modernism and negativity is one that remains largely uncontested (Levenson, “Introduction,” 2). In spite of their recognition of the “badness of things,” modernists were by no means disinterested in ideas of happiness and the good life (Mao, “Troubled,” 20). As I will illustrate through two examples in the final section of this essay, this particular grand narrative has informed the kinds of texts that have been lauded and canonized, and which have remained on the periphery or entirely unseen. Tellingly, and as my examples show, it is often the work of women that has been elided on these grounds. Thus, the privileging of negativity in modernist studies is connected in various ways to the gendering of modernism.

The Fate of Happiness

The lack of attention in modernist studies to ideas of happiness is, I want to propose, an effect of the diminishing status of happiness in the history of Western philosophy from the nineteenth century to the present time. In short, from the late eighteenth century, happiness became unfashionable, trivial. To speak of the changing fate of happiness is to engage in a pun on the word, as there is a long historical association between happiness and luck, fate, or fortune. The Greek term for happiness, eudaimonia, comprises the Greek eu (good) and daimon (god, spirit, demon), thus containing within it the idea of good fortune, “guiding spirit,” and being favoured by the gods (McMahon, Happiness, 3). The root of happiness in Middle English and Old Norse is happ, meaning chance or fortune, as reflected in terms such as “happenstance” and “haphazard” (11). According to McMahon, this association is true for “virtually every Indo-European language” (10). However, in recent times the usefulness of happiness as an idea, and its desirability as an ideal, has come under critical scrutiny.[21]

In Mourning Happiness: Narrative and the Politics of Modernity, Vivasvan Soni traces the role of narrative in concepts of the good life and the changing status of happiness from the Classical period to the twentieth century. He observes that while in the Classical period happiness was a political concept tied to the public realm and the ethical life, from the eighteenth century it became increasingly aligned with pleasure and bourgeois values. This privatized version of happiness was met with much criticism in the nineteenth century:

At least as commonplace as the narrative of the eighteenth century’s obsession with happiness is the narrative of the nineteenth century’s hostility toward happiness. By this time, happiness has become what Fredric Jameson has called “bourgeois complacency”: it designates a purely narcissistic interest in one’s private well-being, devoid of political content. Once the concept of happiness has become thoroughly banal and sentimentalized, a range of negative affects such as anxiety, despair, boredom, suffering, and melancholy are privileged instead. The promise of authenticity and critical self-consciousness now lies in negativity, from Hegel and romanticism to Kierkegaard and Heidegger. To care about happiness is to settle for the superficiality of everyday concerns rather than the intense and sublime experiences of negativity.[22]

As a feminist critic whose work has focused on recuperating the everyday and ordinary as sites of value and philosophical and political significance, I am both intrigued and troubled by an androcentric, intellectual history that disavows happiness the moment it becomes domesticated and private. As I and other feminist critics have argued, the fiction and life writing of authors including Virginia Woolf, H.D., and Francis Partridge complicate simplistic claims that a valuing of private happiness and the domestic is necessarily a depoliticized stance or act, particularly during social crises such as wartime.[23] In one of only two essays on Virginia Woolf and happiness, Kirsty Martin observes that in her diaries of the early years of the Second World War, Woolf repeatedly describes the necessity of creating and building moments of private happiness as a kind of “bulwark” against the collective trauma of war.[24] Crafting moments of private happiness becomes an act of resilience and resistance in the face of the ongoing trauma and misery of wartime (409).

Nevertheless, according to the historical trajectory described by Soni, with the “political eclipse” of happiness during the eighteenth century, happiness loses its philosophical and political status and can no longer be of service to the project of the authentic, heroic modern self, which is now realized through negativity and suffering (Soni, Mourning Happiness, 4). McMahon agrees that in the eighteenth century happiness became aligned with pleasure or good feeling and that philosophers such as Kant in his Groundwork for the Metaphysics of Morals (1785) began to reflect on the troubling disconnect between being good (virtue) and feeling good (happiness) (McMahon, Happiness, 251). Doing the right thing isn’t always pleasurable, and pleasure by no means ensures right action.

While McMahon’s study charts a more extensive intellectual history of happiness than Soni’s—one that takes account of the utopian and socialist models of happiness that were circulating in Europe, Britain and America from the late eighteenth century—he also notes the fashioning of various negative affects from the eighteenth century onwards. This included terms for new forms of modern feeling such as Werthersfieber (“Werther’s fever”), which expressed a “veritable cult of misery among disaffected youth” inspired by Goethe’s Sorrows of Young Werther (1774) (McMahon, Happiness, 275). Similarly, Weltschmerz, coined by the German poets Heinrich Heine and Jean-Paul Richter, came over the course of the century to connote “world weariness, or literally ‘world pain,’—the acute anguish brought on by the simple fact of being in the world” (McMahon, Happiness, 275). The writings of Jean-Jacques Rousseau, François-René de Chateaubriand, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Percy Shelley, Lord Byron, John Keats, and many others exemplify the fashioning of troubled feeling during the Romantic period such as melancholy, spleen and ennui. McMahon contends that “[t]he same century that consolidated happiness as an earthly end also bred new forms of despair” (276). It is, he writes, to “Romanticism that we owe the still-powerful, if deeply insidious, myth that the true man of feeling, the artist, the intellectual, must by definition be a suffering soul,” as suffering was viewed as the right response to a deeply imperfect world (282, 284).

Corresponding with Soni’s analysis, McMahon argues that a diminishing value was attached to the search for happiness in the second half of the nineteenth century due to the influence of Romanticism and the philosophy of “the greatest pessimist in the Western tradition,” Schopenhauer (298). Thus, according to these intellectual histories, since the nineteenth century happiness has been unfashionable and even deemed by some philosophers and critics as anti-intellectual, as a philosophical preference for scepticism took hold. In recent decades, French philosophy in particular has responded more affirmatively to the contemporary “turn” towards happiness, but critical theory—the field that exerts more influence on literary studies—continues to cast a sceptical eye on happiness and its close cousin, optimism.[25]

Indeed, several decades ago, Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick observed the “unintentionally stultifying side effect[s]” of a methodological privileging of negativity and suspicion in queer theory and critical theory more broadly.[26] She argues that while Paul Ricoeur’s intention in his account of the “hermeneutics of suspicion” (which he links to the thought of Marx, Nietzsche and Freud), was “descriptive and taxonomic rather than imperative,” in late twentieth-century theory a hermeneutics of suspicion was “widely understood as a mandatory injunction rather than a possibility among other possibilities” (125). Such a critical landscape perceives “anything but a paranoid critical stance” as “naïve, pious, or complaisant” and occludes other kinds of cognitive and affective theoretical practices, including reparative ones.[27] The scholarly privileging of negative affect and suspicious and paranoid reading practices coincides with what Charlie Tyson has recently described as a culture of “apocalypse chic” in the academic humanities whereby a “pessimistic certainty” has “become a recognizable style of thought.”[28] Fatalism, he suggests, has become “fashionable,” a weariness propelled both by the current state of the world and the troubled state of the humanities.

Aesthetic seriousness, scepticism, world weariness, “critical self-consciousness,” intellectual integrity, the redemptive power of art—these are some of the most familiar terms through which canonical modernism has been described, and it is difficult to discern which is the chicken and which is the egg in this equation (Soni, Mourning Happiness, 4). The changing fate and intellectual history of happiness—as described by critics such as Soni and McMahon—have informed how modernism has been understood and conceptualized in the academy and beyond, and the paranoid reading practices favoured in the critical humanities since the late twentieth century have encouraged a continued focus on modernism’s troubles and negativity. Moreover, our contemporary global state of worry and crisis influences how we continue to imagine and engage modernist texts: it is a self-affirming negative feedback loop.

However, modernism and its surrounding cultures were far from disinterested in the question of happiness and wellbeing. This interest is reflected in psychological, medical, political, popular, and artistic contexts of the period. For example, the psychologist J. C. Flügel’s “A Quantitative Study of Feeling and Emotion in Everyday Life,” published in the British Journal of Psychology in 1925, comprised the first attempt to scientifically measure people’s daily happiness, and investigated the sorts of affective states most aligned with pleasure (which included interest, joy and contentment) and unpleasure (notably anxiety, worry and fatigue).[29] This scientific interest coincided with the emergence of a large volume of popular literature in the 1920s that “promoted happiness as a goal” and advised how “individuals could achieve the goal through their own concerted effort.”[30] Indicative titles included 14,000 Things to Be Happy About and 30-Day Plan: 101 Ways to Happiness (45). According to Martin, “building happiness and struggling to maintain it against a background of continuing suffering echoes a particular strand in contemporary thinking” in Britain that shaped the post-World War One period (“Happiness,” 397). “There were,” Martin continues, “frequent suggestions from doctors and politicians that happiness might be considered as a public health issue,” and that the prevention of “mental distress” was a national concern—a theme that she explores in the context of Woolf’s novel Mrs Dalloway (398). In The Self-Help Compulsion, Beth Blum traces the complex and ambivalent relationship between modern literature and the self-help industry which, she writes, was a “commercial juggernaut” by the turn of the twentieth century.[31] Blum explores modernism’s resistance to, but also entanglements with, this new industry and the ways in which modernist literature has, somewhat ironically, become a popular source in recent years for self-help guides (Self-Help, 16–24).

Modernist writers and artists explored ideas and forms of happiness that responded to their particular conditions of modernity. As I will outline through some examples below, in a context of ongoing social change and political and existential uncertainty, modernists acknowledged the complexity and sometimes precarity of happiness in modern times. They explored new aesthetics of happiness. As opposed to reaching for Classical models that viewed happiness as something determined retrospectively, based on the narrative arc of a life, or repudiating its move to the sphere of the prosaic, many moderns embraced a happiness that was connected to the episodic and everyday.[32] If, as the speaker in the first of Rilke’s Duino Elegies proclaims, “Every single angel / is terrible!” and Eliot’s speaker in The Waste Land says “[t]he nymphs are departed,” perhaps happiness can be found in the quotidian of “What’s left”:

Maybe some tree

on a hillside

one that you’d see every day

and the perverse loyalty

of some habit

that pleased us

and then moved in for good.[33]

Here, Rilke’s habit—habit being by nature an episodic act that is repeated over time—both becomes a source of the good (it pleased us) and a source of continuity that makes us feel that little bit more at home in the world (“moved in for good”). Rilke’s speaker seeks not the loyalty and good graces of the gods, but the loyalty and persistence of trees and habits. In the past decade or so, modernist studies has recognized the importance of the everyday and ordinary to modernist aesthetics and philosophy.[34] As my examples will illustrate, it is often within the sphere of the immanent and everyday that happy modernisms have been hiding in plain sight.

Happy Discoveries

Once the question of modernism and happiness began to preoccupy me, I started to see expressions, intimations, or hopes for it everywhere. I was surprised when I turned to, of all authors, Jean Rhys, to find happiness (or its absence) to be a recurring preoccupation. Indeed, Jean Rhys is one of the modernist writers to have received the most scholarly attention on this topic: perhaps because her writing problematizes happiness, thereby reconfirming the scepticism towards positive feeling in modernist studies and critical theory.[35] As Paul Ardoin notes in his essay on Rhys and un/happiness, one of the most familiar themes in Rhys’ work is “the embrace of unhappiness by the ‘bad’ or ‘wicked’ woman” (“The Un-happy,” 233). However, as Ardoin goes on to argue, Rhys is very much concerned with the politics and ethics of happiness.

In Voyage in the Dark, the protagonist Anna Morgan repeatedly reflects on states of happiness (which often centre on memories of her childhood in the West Indies), and self-consciously assesses her current state of happiness or sadness in England: “‘When he kisses me, shivers run up my back. I am hopeless, resigned, utterly happy. Is that me?’”[36] Reflecting Anna’s fractured and sometimes dissociated sense of self, the subject and object of happiness can become blurred: “We had another bottle of wine and I felt it warm and happy in my stomach” (19). For Anna, happiness is a risky, precarious state—constantly heralding the threat of its passing, always teetering on the edge of sadness:

Then I remembered that I hadn’t got to get up and go away and that the next night I’d be there still and he’d be there. I was very happy, happier than I had ever been in my life. I was so happy that I cried, like a fool.

I kept thinking, “It’s unlucky to know you’re happy; it’s unlucky to say you’re happy. Touch wood. Cross my fingers. Spit.” (66, 68–9)

Anna’s reflection recalls the happ that is central to the etymology of happiness. She fears that acknowledging one’s happiness might bring bad luck or ill fortune and so she performs a series of rituals to try and appease the gods or fates. In the novel this superstitious worldview is informed by Anna’s West Indian heritage as opposed to a Classical or Western one. Her reflections also anticipate Ahmed’s observation that “when we become conscious of feeling happy (when the feeling becomes an object of thought), happiness can often recede or become anxious” (Ahmed, The Promise, 25). For the young and impoverished Anna, happiness is not something stable or safe but anxious and uncertain, seemingly out of her control.

Elsewhere in Rhys’s fiction, happiness is figured as the kind of social “duty” that Ahmed interrogates in The Promise of Happiness, a project that traces “the unhappy effects” of a happiness that is used to “redescribe social norms”—such as heterosexual marriage—“as social goods” (7, 2). As Ardoin notes, “[w]hat Ahmed theorizes in 2010 is already familiar to readers of Rhys,” a point that emphasizes how we have perhaps looked to particular areas of modernism that confirm our view of happiness as something already lost or deferred for the moderns, thereby hindering our capacity to see the forms that happiness does take in the literature and art of the period (Ardoin, “The Un-happy,” 234). In Voyage in the Dark, a text that is concerned with ideas of social performativity and mimicry, Anna the demi-monde is frequently coerced to appear happy or to put on a happy mask for the benefit of those around her. Thus Walter, Anna’s older lover, addresses Anna:

“Well, look happy then. Be happy. I want you to be happy.”

We went out into the street to say good-bye to them. I was thinking it was funny I could giggle like that because in my heart I was always sad, with the same sort of hurt that the cold gave me in my chest. (Rhys, Voyage, 44, 14)

Walter’s injunction to Anna to “look happy,” recalls the title of Rhys’s unfinished autobiography, Smile Please, which refers to Rhys’s childhood memory of being instructed by her mother to “[k]eep still,” as a photographer encouraged her to “[s]mile please” and look “[n]ot quite so serious.”[37] From a very young age, Rhys aligns happiness with social duty and masquerade and illustrates how the “burdens of modernity are compounded by the need to keep smiling” (Stearns, Satisfaction, 6). Similarly, the smile and laughter take on unfamiliar meanings and resonances in her fiction, with laughter in particular often being aligned with cruelty (see Rhys, Voyage, 74, 106).

Rhys’s fiction anticipates feminist and queer critiques of dominant narratives of the good life, highlighting their exclusionary nature or their unattainability—what Lauren Berlant describes as the “cruel optimism” of the happiness myths and false “promises” promulgated by capitalist society (Berlant, Cruel Optimism, 24, 28).[38] In particular, Rhys highlights the precarity of conventional models of happiness for women who inhabit but exist on the margins of cosmopolitan modernity due to their race, age, and/or class. Her fiction also explores the implications of resisting the normative, socially sanctioned models for flourishing and the good life that were prescribed for women at the time. As Ardoin observes, “married Rhys characters from Quartet to Wide Sargasso Sea repeatedly belie the idea of marriage as a calm, happy paradise,” and her characters will frequently “turn antisocial and try to chart an individual happiness in spite of or specifically against expectations” (Ardoin, “Un-happy,” 235, 243). Rejecting the purportedly happy teleologies of marriage and “getting on,” Rhys’s protagonists choose stasis, passivity, and recursiveness, thereby staging a radical critique of contemporaneous gendered and capitalist models of the good life.[39]

In a novel that rejects the logic of the bildungsroman and modernity’s commitment to progress and forward movement, at the conclusion of Voyage in the Dark, after nearly dying from a botched abortion, Anna wakes to imagine a future of repetition:

When their voices stopped the ray of light came in again under the door like the last thrust of remembering before everything is blotted out. I lay and watched it and thought about starting all over again. And about being new and fresh. And about mornings, and misty days, when anything might happen. And about starting all over again, all over again. (Rhys, Voyage, 159)

Like Sasha Jansen in Good Morning, Midnight (1939), Anna seems to occupy a world that “prohibits any meaningful change” and in which “repetition takes on a primal or mythic quality.”[40] From the time of the Ancient Greeks, theories of happiness in Western culture have privileged a model of teleology and linear narratives.[41] Such models come under scrutiny and aesthetic pressure during the modernist period, as writers and artists rethought the nature of happiness under their particular conditions of modernity. This is perhaps why the episodic (memories, the epiphany, the pleasure of a habit), as opposed to linear narratives or the full narrative arc of a life, are the privileged form and vehicle for happy feelings during the modernist period.

Rhys’s work has historically been read through the affective prism of shame, depression, sadness, and trauma.[42] However, through her exploration of negative affect, Rhys offers many perceptive insights on the nature and phenomenology of happiness and the good life. These include the effects of normative happiness scripts and the “social imperative to be happy,” and the possibilities of, and obstacles to, happiness for those marginalized under the forces of Empire, capitalism, and patriarchy (Ardoin, “The Un-happy,” 236).

Like the happ of happiness, modernism’s engagements with the good life also materialized before me quite unexpectedly, in the course of unrelated projects I was working on at the time. While re-reading several volumes of Virginia Woolf’s diary for an essay I was writing on Woolf and spirituality, I was reminded of how frequently she refers to happiness.[43] Happiness takes many forms and definitions in these volumes. In an entry for April 8 1925, she reflects on her “perfect happiness” but also its indeterminacy: “Nobody shall say of me that I have not known perfect happiness, but few could put their finger on the moment, or say what made it.”[44] Here, Woolf observes the sometimes difficulty of pinpointing when happiness happens, or what constitutes it—issues that several philosophers and contemporary critics have noted.[45] In her discussion of the “mobile” and “promiscuous” nature of this signifier, Ahmed writes: “even if happiness holds its place as the object of desire, it does not always signify something, let alone signify the same thing. Happiness may hold its place only by being empty, a container that can become quite peculiar as it is filled with different things” (Ahmed, The Promise, 201–2).

Elsewhere in her diary, Woolf describes happiness as just such a container, a private “treasure” trove filled with the contentment and pleasure that she finds in the commonplace and everyday:

The immense success of our life, is I think, that our treasure is hid away; or rather in such common things that nothing can touch it. That is, if one enjoys a bus ride to Richmond, sitting on the green smoking, taking the letters out of the box, airing the marmots, combing Grizzle, making an ice, opening a letter, sitting down after dinner, side by side, & saying, “Are you in your stall, brother?”—well, what can trouble this happiness? And every day is necessarily full of it. (Woolf, Diary, vol. 3, 30)

In this example, we find not the ecstasy experienced in some moments of being, but a quiet contentment in the everyday and a regard for being present in the moment that recalls both ancient and contemporary understandings of mindfulness.[46] Here, Woolf describes a happiness that is ordinary (“every day is . . . full of it”) and she proposes that through its ordinariness such a happiness is safeguarded from the contingencies of the outside world. In another entry for April 1925, Woolf aligns happiness with continuity and crafting: “Happiness is to have a little string onto which things will attach themselves” (Woolf, Diary, vol. 3, 11). In 1926, while reflecting on her “intense happiness,” she mourns never knowing the “profound natural happiness” that she imagines comes from having children: “It is therefore what I most envy; geniality & family love & being on the rails of human life” (73). Thus, sifting through this volume of her diaries, happiness is not only a recurring topic but an idea that Woolf conceptualizes in a variety of different ways.

Kirsty Martin proposes that Woolf aligns happiness with creativity, crafting and “making,” and she argues that Woolf’s work is “deeply concerned with exploring the possibility, the practicalities, and the politics of creating happiness” (Martin, “Virginia Woolf’s”, 396). Martin acknowledges that in the popular imagination and critical literature, Woolf is “known much more for extreme unhappiness than for any efforts towards contentment,” a point that illustrates the kind of critical biases I am suggesting need to be redressed (394). Woolf’s suicide and struggles with mental illness have long overdetermined how her fiction and non-fiction are read by both scholars and the general public, a fact powerfully illustrated by Michael Cunningham’s novel The Hours and its subsequent film adaptation.[47] The film begins and ends with Woolf’s suicide, as if this is the determining framework through which we can best know and understand her. As a Woolf scholar who has focused on her engagements with the forms of daily life and ordinary experience, I feel that she would have been appalled by such a narrative framing of her life. As my examples above show, her diaries and also her fiction are replete with accounts of, and critical reflections on, happiness, contentment, pleasure, and joy.[48]

The above comments begin to sketch out a few of the many and varied ways in which Rhys and Woolf engage with the idea of happiness, and the rich possibilities their writing presents for new studies on the topic. The work of other writers including James Joyce, Katherine Mansfield, May Sinclair, and Wallace Stevens, reveal happiness and human flourishing as topics of serious interest and contemplation. The modernist epiphany, with its basis in states including ecstasy, joy, contentment, plenitude, presence and satisfaction, is principal evidence that happy modernisms have always been hiding in plain sight. As my in-progress book on this topic seeks to demonstrate, while many modernists questioned modernity’s key happiness scripts, they by no means gave up on the philosophical idea of the good life.

Unhappy Effects

In addition to overlooking a rich topic in modernism, there are other implications to the field’s suspicion of positive affect, one of which relates to processes of critical reception and canon formation. Reflecting on some of the female photographers and artists that I have researched and published on over the years, such as Ethel Spowers, Helen Levitt, and Margaret Monck, expressions of happiness, joy and related affects form a significant part of their representations of modern, urban experience. Tellingly, the work of these artists has remained marginal and, in the case of Monck, is little known. It suggests to me that the privileging of negativity has undergirded processes of canon formation and perhaps even the kind of recovery work that has been undertaken in recent decades.

The art of Ethel Spowers and some of her Australian female contemporaries provides an illustrative example of this effect. Spowers was a Melbourne-born and based illustrator, painter and printmaker. Along with Dorrit Black, she was instrumental in supporting and promoting modern printmaking in Australia during the 1920s and 1930s and had a long and successful career in Australia and overseas. For approximately three months from late 1928 to early 1929, and again for a period in 1931, Spowers studied at the Grosvenor School of Modern Art under the instruction of Iain Macnab and Claude Flight.[49] Claude Flight was Britain’s most enthusiastic promoter of the modern linocut. As such, the linocuts produced by Spowers and her Australian peers, Dorrit Black and Eveline Syme (who also studied at the Grosvenor School), have generally been assessed in the context of Flight’s aesthetic vision, even though there are significant differences between the approach and style of their work.[50] For example, the linocuts of Flight and Cyril E. Power, who was another founding member of the Grosvenor School, adopt an aggressive and highly compressed visual aesthetic that was informed by Futurism and Expressionism.[51] Their designs are characterized by sharp lines, distorted forms, and sometimes explosive visual rhythms that express the speed and intensity of modern, metropolitan life. As illustrated in his 1922 linocut “Down the Strand,” Flight’s generic figures often symbolize the alienated, anonymous worker or soldier. Power’s fierce, “sardonic eye,” typically presents the industrial, urban environment as a hostile, anti-social and dystopian space, as in “Whence & Whither” (1930) and “The Tube Train” (1934) (Coppel, Linocuts, 54).

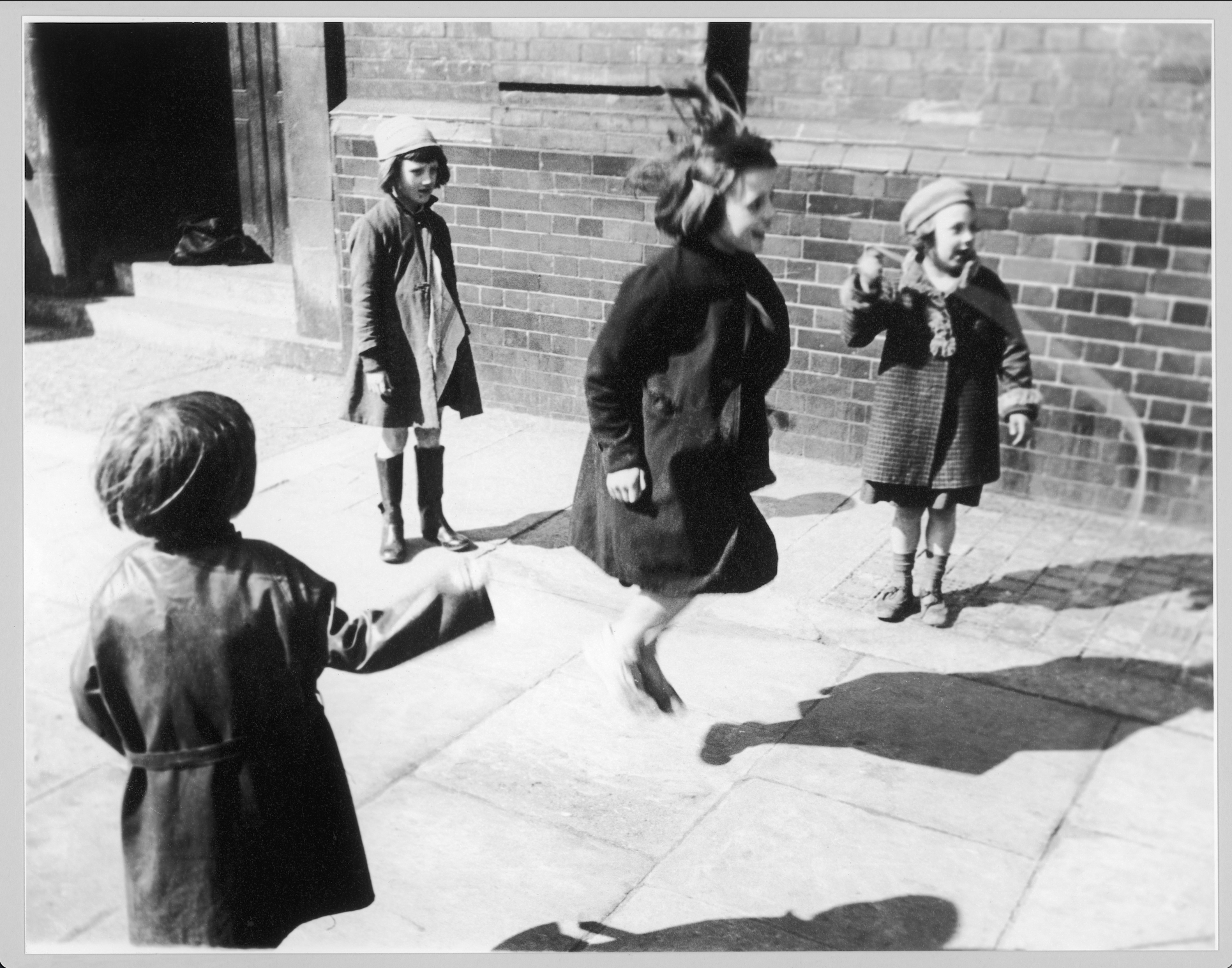

By contrast, Spowers adopts some of the formalist principles promoted by the Grosvenor School, such as rhythmic design, to very different ends. Her use of bold color and organic visual rhythms create what I have described elsewhere as “choreographies of community.”[52] Like her oeuvre more broadly, the subject matter of her color linocuts focus on children at play and scenes of social intimacy and connection. As we see in “The joke” (1932) and “Fox and geese” (1933), many of her designs depict happiness, laughter, joy and freedom of movement: there is no conflict, distress, alienation or angst (figs. 1 and 2). The affective range and tone of Spowers’s work is a complete contrast to her English and European contemporaries at the Grosvenor School, and her strikingly positive vision of modern everyday life offered an Antipodean challenge to the dominant discourses of modernity predominant in much British and European modernism at the time.

In spite of her considerable success during her lifetime, and her talent as a printmaker and designer, Spowers’s work fell into obscurity until quite recently. As Sandra Robertson observed in 1985, “[o]nly since the mid-1970s have [Spowers’s] linocuts been intermittently re-exhibited in joint exhibitions. While her place in the history of Australian art has not gone unnoticed, it has gone unassessed and not fully acknowledged.”[53] While the color linocut is a medium that has received little attention in modernist studies and art history, I’m convinced that the lack of scholarly attention to Spowers is due to the tone, mood and subject matter of her work. The critical framing of her art is instructive in terms of my argument about modernist studies’ eschewal of happiness.

For example, in his excellent study, Linocuts of the Machine Age: Claude Flight and the Grosvenor School, Stephen Coppel describes the linocuts of Black, Syme, and Spowers as presenting a “milder form of modernism” as compared to their British and European contemporaries—a euphemism that I take for “soft” or possibly feminine (Coppel, Linocuts, 66). He makes this comment whilst acknowledging that these women “demonstrated a mastery of the medium” that “surpassed” that of Flight (66). While noted as technically superior, the prints of Spowers, Syme and Black are, nevertheless, assessed in terms of their failure to replicate the aggressive avant-garde aesthetics and gritty worldview of their British, and predominantly male, contemporaries.

Another implicit and gendered criticism that has been leveled against Spowers’s art and that of other Australian women artists including Margaret Preston and Thea Proctor, is that it is “essentially escapist” (Robertson, “Ethel Louise Spowers,” 57). Through this comment, Sandra Robertson criticizes Spowers’s art for failing to engage with the harsh social realities faced by many Australians during the 1930s. Robertson goes even further, claiming that Spowers’s art is “devoid of social comment”—a surprising claim when one considers that a principal focus of her oeuvre is social relations and social connection (57). Robertson makes this appraisal while acknowledging that much of the inspiration for Spowers’s art comes from “ordinary incidents” and the stuff of daily life (“children playing, bank holidays or football, architectural and landscape themes”) (57). This critical trend is echoed by leading Australian art historian, Roger Butler, who stated that many of the women artists affiliated with the Grosvenor School who produced linocuts in Australia in the 1930s “had independent means and were unaffected by the economic depression, while others made images of domestic tranquillity and prosperity that denied any suggestion of the larger social issues” (Butler, “The Grosvenor School,” 205).

The shared attitude implicit to these assessments is that modernist art that deals with affirmative feelings or themes, or a domesticated version of “tranquillity,” is apolitical, and according to Coppel, not modernist in the “strong” sense. The above critiques regarding a purported lack of social commentary by these women in their art recall my earlier discussion of the nineteenth-century critique of modern ideas of happiness that centred on the private sphere, pleasure, and the domestic—Jameson’s “bourgeois complacency” (Jameson quoted in Soni, Mourning Happiness, 3). It is telling, and to me problematic, that these examples of modernism are criticized aesthetically and ideologically for failing to represent negative experience or social problems in their representations of modern life, as if modern life is, by definition, always and only trouble and troubling. Perhaps it is a defensive hangover from the field’s long campaign to counter mid-twentieth-century accusations of modernism’s apoliticism and escape from real life into the realm of aesthetic autonomy. But as histories of happiness testify, happiness is never separate from questions of the political or ethical. The only other critic who has treated the affirmative outlook of Spowers’s art positively is Tracey Lock:

[Spowers’s] subject matter is consistently affirming, showing an affinity with the joy that she experienced through observing everyday physical activities such as children at play. In this way, her themes provide relief from the darker and pervasive forces that towered across her time such as the Great Depression and World War II (Lock, “Relaxing the Line,” 73).

“[P]ervasive” and “towered” again implies that the “darker” forces overwhelmed modern life in the 1930s, and that Spowers’s art captured the brief glimpses of relief. But, in fact, and like some of the other examples I’ve discussed, Spowers’s art depicts happiness as a part of ordinary life, not anomalous.

By way of one further example, the photography of Margaret Monck tells a similar story of the relationship between modernism, mood, and critical uptake. Monck’s documentary photography, like Woolf’s diaries and Spowers’s linocuts, illustrates that it is often in women’s work—work concerned with quotidian themes and genres (the diary, the candid photograph)—that positive feeling is shown to be a normal part of modern life, not just an exception to darker, pervasive moods. A street photographer who was active during the 1930s and early 1940s, Monck documented London’s working-class districts, particularly areas in the East End and around the docks. Monck was very much connected to the documentary film and photography scene in England. She was the wife of the film director and editor, John Monck, who worked on Robert Flaherty’s 1934 documentary film Man of Aran.[54] Largely self-taught as a photographer, Monck knew Edith Tudor Hart, the sister of Wolfgang Suschitzky, and spent a brief period under the tutelage of Hart honing her skills in enlarging, developing and printing.[55] Monck came from the British peerage but rejected that life and destiny.[56] Listening to her extensive interview with Val Williams, one gets the impression that she was down to earth, irreverent, against snobbery and privilege, and extremely self-effacing about her work.

Monck’s photography was unknown to the public until the 1980s, when Val Williams recovered her career and those of other early twentieth-century British female photographers for her project, Women Photographers: The Other Observers 1900 to the Present. Monck “explor[ed] London” by foot and took photographs in some of the most economically depressed areas of the city: districts including Bethnal Green, Poplar, Brixton, Soho, and Limehouse (Monck interview, cassette 2, side 1). When one views her archive of approximately 200 prints at the Museum of London, the thing that is immediately striking is the way in which they break from the photography of social concern that was popular in Britain and America at the time, and had been since the 1890s. Some contemporaneous examples of this genre of photography by Cyril Arapoff are contained in one of the Monck files, and vividly display their contrasting approaches.[57] As Alan Trachtenberg has said of the New York street photographer Helen Levitt, Monck presents her subjects “entirely on their own terms,” not as victims or spectacles for the curious middle-class observer.[58] Monck’s images reflect the pride that her subjects felt in regards to their skills, trades, produce, and businesses (fig. 3).

Other recurring subject matter in her work is the sociality of the street, community life, and (again, like Helen Levitt) the play and games of children: “I had a feeling for children and I love seeing them enjoying themselves” (Monck interview, cassette 2, side 1) (figs. 4–6). Indeed, in many of the examples I have discussed in this essay, children and/or the experience of childhood (for Rhys via memory), are recurring sites of happiness.

In her interview with Williams, Monck speaks of her great respect for the working classes, particularly the women. When asked about the economic deprivation in the East End, Monck replied that she “felt that the women of the family were absolutely heroic because they saw that their children went out with warm clothes and you never felt that they’d gone without a meal; but you knew perfectly well that somebody had to go short and one knew that it was the mother” (Monck interview, cassette 2, side 2). “Everybody,” she continues, “kept the highest standard they possibly could whatever the circumstances” (cassette 2, side 2). Unlike social documentary photographers such as Arapoff and Walker Evans/James Agee for the project Let Us Now Praise Famous Men (1941), Monck never imposed on people’s privacy by going inside their homes: “I didn’t want to intrude on their privacy and I didn’t have flashlight” (cassette 2, side 2). She was also uncomfortable with the idea of photography functioning as a vehicle for a photographer’s own political agenda or cause. As she explained to Williams: “my photographs show that I was never prepared to say I am a Communist and let me show you this, you know, I wanted to show things as I’d seen them but I didn’t want to rub the things in” (cassette 2, side 2). In regards to the value of her images, she reflected: “I can’t see anything in my life that has given me to think that any of my shots are particularly important. What I think is important is the fact that they were taken because they were there at that date” (cassette 2, side 1).

In general, the mood of Monck’s photographs spans the positive, to the contemplative or neutral. During her lifetime it seems that very few of her photographs were published. The one that was most circulated is something of an anomaly in her oeuvre. The image comes from a series of three photographs that Monck took across from Charlie Browns in Limehouse, East London in 1937. Figure 7, which captures all of the familiar tropes about the urban poor, misery and entrapment, was used as a card by the Housing Office, presumably to raise awareness about the living conditions in the East End, or to buttress council and government campaigns at the time for urban clearances and renewal (fig. 7).[59] While it appears that the Mass Observation commissioned Monck to document the clearance of working-class homes for new high-rise flats in St Johns Wood—this picture from Limehouse is the only image by Monck that garnered much interest during her lifetime (Monck interview, cassette 3, side 1). As the contemporary quip goes, “if it bleeds, it reads.” According to Monck, opportunities for publishing “didn’t come [her] way” and there wasn’t much of an “opening” for the kind of work she wanted to do (cassette 3, side 1).

Like Helen Levitt’s New York street photography, Monck’s oeuvre constitutes an understated but significant challenge to long-standing middle-class assumptions, as well as government, social reformist and popular propaganda, about the daily lives of the urban poor during the 1930s and 1940s. While of course selective, her images offer a non-sensationalist visual history of everyday life in London’s working-class districts, a version of history that has been much less frequently recorded or circulated. Children playing, someone walking home from a factory, a woman selling fish, neighbours chatting on the street, a man completing some street art on a pavement, two women chatting outside their homes—her preference is for the prosaic and non-sensational. Her approach also resists the aestheticization of the slum that Saidiya Hartman critiques in Wayward Lives. Hartman imaginatively represents the reflections of a young black girl in the early 1900s as she leans out the window of her third-floor window looking at the “reformers and sociologists” snapping pictures below: “They take a picture of Lombard Street when hardly no one is there. She wonders what fascinates them about clotheslines and outhouses. . . . Are the undergarments of the rich so much better?”[60] These reformers “come in search of the truly disadvantaged failing to see her and her friends as thinkers or planners, or to notice the beautiful experiments crafted by poor black girls” (4). Quietly, unobtrusively, Margaret Monck recorded the achievements and successful experiments of people living in London’s slums. I find it telling that there has been little uptake of her photography since its rediscovery by Williams in the mid-1980s. While this might be in part due to the relatively small scale of the archive, I suspect it has more to do with the mood, tone, and approach of her work.

The candid street photography of Helen Levitt and Margaret Monck and the work of Australian artists such as Ethel Spowers and Thea Proctor, point to an overlooked affective counter-canon in modernism. It is one that figures happiness and positive experience not as anomalous, naive, or apolitical, but ordinary: a part of the tapestry of daily life, like the moments that Woolf attaches to her imagined happiness “string.” Importantly, these representations are not class-specific; they range across working and middle-class cultures and span both the private and urban spheres.

Coda: Troubled Times

I first drafted this essay in 2020 during a time when it was challenging to think about the good life. Where I live and type this essay—in the Blue Mountains on the outskirts of Sydney, Australia—late 2019 and 2020 felt nothing short of apocalyptic. It started with drought, catastrophic bushfires (which smoldered just two kilometres from my home), followed shortly thereafter by flooding and landslides. Eighty percent of the Greater Blue Mountains World Heritage Area was burnt. These environmental catastrophes were succeeded by the COVID-19 pandemic, civil unrest in the US, a global economic depression, all against the backdrop of an increasingly polarized and nationalistic geopolitical landscape. In our extremely troubled times, it can be difficult to contemplate and research happiness and what it means. It may even strike some as ethically suspect. This is no doubt why critical moods such as pessimism and suspicion have become predominant in the humanities.[61]

In his keynote paper for the “Troublesome Modernisms” conference, Douglas Mao notes that contemporary literary scholarship sees one of its principal tasks and responsibilities to be to identify what is wrong in the world and demonstrate the ways in which works of literature trouble the status quo (be it in social, cultural, economic, activist or political terms): “While we may take part of our task to be showing how our texts reveal what’s good and lovely in the world, we tend to take as our more serious and significant work that of showing how our texts illuminate what’s not good in the world” (Mao, “Troubled,” 17). The diagnostic work that Mao describes here coincides with the tradition of negative critique that I discussed previously in this essay: but it is important to emphasise that, in his own work, Mao most certainly takes the business of showing what is good in the world, seriously. While I am by no means suggesting that the diagnostic aims of contemporary literary studies are not important and necessary, I concur with the call of critics including Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick and Rita Felski for literary studies and critical theory to “embrace a wider range of affective styles and modes of argument” in order that we can avoid travelling down “prescriptive” and “predetermined” critical paths that risk foreclosing our minds to “the play of detail, nuance, quirkiness, contradiction, [and] happenstance” both within texts and in the context of their wider cultural and historical milieus (Felski, Limits, 3, 34). I want to end this essay with two concluding comments as to why I think a turn to happy modernisms, and by extension, more affirmative readings of modernist literature, art and culture, is important and useful at this juncture.

Firstly, as we are in the midst of a happiness and wellbeing turn in the culture at large, I think it is incumbent upon us as scholars in the humanities to engage with the idea of happiness (and other positive affects) in ways that are not only suspicious but also creative and constructive. If not, we risk leaving the future of happiness as an idea to the social policy makers, positive psychologists, politicians, celebrities, and social influencers. The critique of hegemonic capitalist and neoliberal narratives of the good life offered by queer and feminist theorists such as Lauren Berlant and Sara Ahmed are necessary and incisive, and their studies recruit modernist literature as part of their critique. However, I am proposing that modernism—with its strong roots in the history of philosophy and religion, its profound insights into the complexity, range and idiosyncrasy of human experience, and its resistance to grand narratives of all kinds—can surely offer us new terms for thinking about what happiness might mean and look like in the modern world.

Secondly, there are many ways in which the modernity of the early twentieth century mirrors the conditions of our contemporary modernity: for example, political polarization and the rise of far-right politics, a growing epidemic of loneliness and anxiety, global pandemics, economic precarity, international conflicts, and fear of annihilation and/or the collapse of civilization as we know it. In the archives and overlooked corners and stoops of modernist literature, art, and culture we might well find alternative accounts and ways of thinking about happiness and human flourishing that will assist us in grappling with the challenges of our own troubled historical times. For decades we’ve looked to the moderns as a mirror to our own angst, trauma, and skepticism. Through fostering a different critical perspective and mood, what might our modernist predecessors have to tell us about the pursuit of happiness and the good life during troubled times?

Notes

I would like to express my sincere thanks to the two anonymous readers at Modernism/modernity for their excellent and incisive feedback during the peer review process. I’m deeply grateful to Doug Mao, Alix Beeston, and Duncan Graham for their generous and thoughtful engagements with an earlier version of this essay and the larger project.

[1] Sara Ahmed, The Promise of Happiness (Durham: Duke University Press, 2010), 3.

[2] While books on the topic are too numerous to mention, podcasts include Laurie Santos, The Happiness Lab, Gretchen Rubin, Happier, Dan Harris, Ten PerCent Happier, Shay Jetty, On Purpose, and the Stephanie and Jonathan Fields, Good Life Project.

[3] According to McMahon, prior to the eighteenth century, “[n]o previous age . . . wrote so much on the subject or so often” (Happiness: A History [New York: Grove Press, 2006], 200).

[4] James Ellsmoor, “New Zealand Ditches GDP for Happiness and Wellbeing,” Forbes, July 11, 2019. Following Bhutan’s example, many countries including the UK, US and Italy have introduced wellbeing indexes; see C. Wright, “Against Flourishing: Wellbeing as Biopolitics, and the Psychoanalytic Alternative,” Health, Culture and Society 5, no.1 (2013): 20–35, 21.

[5] See Wright, “Against Flourishing” and William Davies, The Happiness Industry: How the Government and Big Business Sold Us Well-Being (London: Verso, 2015).

[6] Quoted as the epigraph in Will Ferguson, Happiness TM (Edinburgh: Canongate, 2002).

[7] See, for example, Paul Ardoin, “The Un-happy Short Story Cycle: Jean Rhys’s Sleep It Off, Lady,” in Rhys Matters : New Critical Perspectives, ed. Mary Wilson and Kerry L. Johnson (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013), E-book, 233–248; Andrew Kalaidjian, “‘The Good Life Will Start Again’: Rest, Return, and Remainder in Good Morning, Midnight,” in Rhys Matters, ed. Wilson and Johnson, 213–232; Justus Nieland, “Making Happy, Happy-making: The Eameses and Communication by Design,” in Modernism and Affect, ed. Julie Taylor (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2015), 203–225; Wendy Truran, “Feminism, Freedom and the Hierarchy of Happiness in the Psychological Novels of May Sinclair,” in May Sinclair: Re-Thinking Bodies and Minds, ed. Rebecca Bowler and Claire Drewery (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2017), 79–97; Wendy Truran, “Affective Alchemy: W. B. Yeats and the Transformative Heresy of Joy,” in The Edinburgh Companion to Irish Modernism, ed. Maud Ellmann, Siân White, and Vicki Mahaffey (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2021), 437–51.

[8] David Michael Kleinberg-Levin, Redeeming Words and the Promise of Happiness: A Critical Theory Approach to Wallace Stevens and Vladamir Nabokov (Plymouth, MA: Lexington Books, 2012); Nathan Waddell, Modernist Nowheres: Politics and Utopia in Early Modernist Writing, 1900–1920 (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012).

[9] Here I use the term “furphy” not in the sense of an erroneous or unfounded story, but an exaggerated one.

[10] Douglas Mao, “Troubled,” Keynote Presentation, “Troublesome Modernisms,” British Association for Modernist Studies Conference 2019, London, UK, June 20, 2019, 4, 20. I’m grateful to Professor Mao for sharing a copy of his essay with me. In illustrating the commonplace objection regarding modernism’s privileging of inner turmoil over the social and political reality, Mao draws on examples from György Lukács’s essay “The Ideology of Modernism” (1962) and Chinua Achebe’s essay “An Image of Africa: Racism in Conrad’s Heart of Darkness” (1977). Mao’s essay goes on to examine the relationship between “troubled” and “troubled by” as it pertains to religious experience in modernist literature.

[11] Douglas Mao and Rebecca L. Walkowitz, “Introduction: Modernisms Bad and New,” in Bad Modernisms, ed. Douglas Mao and Rebecca L. Walkowitz (Duke: Duke University Press, 2006), E-book, 1–18, 3.

[12] Mao and Walkowitz, “Introduction,” 11. For an early account of the “[a]cademicism and commercialism” of the avant-garde see Clement Greenburg, “Avant-garde and Kitsch” (1939), in Art and Culture: Critical Essays (Boston: Beacon Press, 1967), 3–21, 9.

[13] Malcolm Bradbury and James McFarlane, “The Name and Nature of Modernism,” in Modernism: A Guide To European Literature 1890–1930, ed. Malcolm Bradbury and James McFarlane (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1976), 19–55, 19, 20.

[14] Herbert Read, Art Now: An Introduction to the Theory of Modern Painting and Sculpture (London: Faber and Faber, 1933), cited in Bradbury and McFarlane, Modernism, 20.

[15] Michael Levenson, “Introduction,” in The Cambridge Companion to Modernism, ed. Michael Levenson (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999), 1–8, 2.

[16] Some examples include Jonathan Flatley, Affective Mapping: Melancholia and the Politics of Modernism (Cambridge, MA.: Harvard University Press, 2008); Madelyn Detloff, The Persistence of Modernism: Loss and Mourning in the Twentieth Century (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2009); Carl Krockel, War Trauma and English Modernism: T. S. Eliot and D. H. Lawrence (Houndmills, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011); Patricia Moran, Virginia Woolf, Jean Rhys, and the Aesthetics of Trauma (New York: Palgrave MacMillan, 2007); Ariela Freedman, Death, Men, and Modernism: Trauma and Narrative in British Fiction from Hardy to Woolf (New York: Routledge, 2013); Julie Taylor, Djuna Barnes and Affective Modernism (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2012), Patricia Moran, “Shame, Subjectivity, and Self-Expression in Cora Sandel and Jean Rhys,” Modernism/modernity 22, no. 4 (2015): 713–34.

[17] Sianne Ngai, Ugly Feelings (Cambridge, MA.: Harvard University Press, 2005), 6, 1, 2.; Allison Pease, Modernism, Feminism, and the Culture of Boredom (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2012).

[18] The theme of the 2022 British Association for Modernist Studies Conference, “Hopeful Modernisms” (June 23–25, 2022, University of Bristol), is one recent example of a gradual shift in the field towards more affirmative modernisms.

[19] Lisa Colletta, Dark Humor and Social Satire in the Modern British Novel (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2003); Susanne Christine Puissant, Irony and the Poetry of the First World War (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2009); Andrew Eastham, Aesthetic Afterlives: Irony, Literary Modernity and the Ends of Beauty (London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2011); Emmett Stinson, Satirizing Modernism: Aesthetic Autonomy, Romanticism, and the Avant-Garde (New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2017).

[20] Lisa Mendelman, Modern Sentimentalism: Affect, Irony and Female Authorship in Interwar America (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2019).

[21] See Ahmed, The Promise; Wright, “Against Flourishing”; Davies, The Happiness Industry; Edgar Cabanas and Eva Illouz, Manufacturing Happy Citizens: How the Science and Industry of Happiness Control Our Lives (Newark: Polity Press, 2019).

[22] Vivasvan Soni, Mourning Happiness: Narrative and the Politics of Modernity (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2010), 3–4.

[23] Miriam Fuchs, The Text is Myself: Women’s Life Writing and Catastrophe (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 2004); Lee Rumbarger, “Housekeeping: Women Modernists’ Writing on War and Home,” Women’s Studies: An Inter-disciplinary Journal 35, no. 1 (2006): 1–15; Angela K. Smith, The Second Battlefield. Women, Modernism and the First World War (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2000).

[24] Kirsty Martin, “Virginia Woolf’s Happiness,” Essays in Criticism 64, no. 4 (2014): 394–414, 409; see also Madelyn Detloff, “Eudemonia: The Necessary Art of Living,” The Value of Virginia Woolf (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2016), 14–28. Both critics emphasise the importance of making and crafting to Woolf’s idea of happiness.

[25] See Ahmed, The Promise of Happiness and Lauren Berlant, Cruel Optimism (Durham: Duke University Press, 2011). For some contemporary philosophical studies that argue for the continued importance of happiness as an idea and aspiration see Frédéric Lenoir, Happiness: A Philosopher’s Guide, trans. Andrew Brown (Brooklyn: Melville House, 2013); Alain Badiou, Happiness, trans. and foreword A. J. Bartlett and Justin Clemens (London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2019); Ype de Boer, “Badiou and Agamben Beyond the Happiness Industry and Its Critics,” Open Philosophy 7, no. 1 (2024): 808–76.

[26] Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, Touching Feeling: Affect, Pedagogy, Performativity (Durham: Duke University Press, 2003), 124.

[27] Sedgwick, Touching Feeling, 126. For a recent discussion of the philosophical and intellectual origins of suspicious reading practices in critical theory and literary studies and the need to increase the “affective range” of criticism, see Rita Felski, The Limits of Critique (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2015), 13.

[28] Charlie Tyson, “Apocalypse Chic,” The Chronicle of Higher Education, August 22, 2019.

[29] J. C. Flügel, “A Quantitative Study of Feeling and Emotion in Everyday Life,” British Journal of Psychology, 15, no. 4 (1925): 318–355.

[30] Peter Stearns, Satisfaction Not Guaranteed: Dilemmas of Progress in Modern Society (New York: New York University Press, 2012), E-book, 45. Stearns’s study focuses in particular on the American context.

[31] Beth Blum, The Self-Help Compulsion: Searching for Advice in Modern Literature (New York: Columbia University Press, 2020), 16.

[32] The Classical idea of happiness proposes that happiness can only be claimed upon a person’s death. It is an assessment made retrospectively by “a community of others,” based upon the narrative arc of a person’s life (Soni, Mourning Happiness, 10). To claim to be happy when alive is “premature, and probably an illusion, for [in the Classical view] the world is cruel and unpredictable, governed by forces beyond our control,” (McMahon, Happiness, 7).

[33] T. S. Eliot, The Waste Land, in Collected Poems 1909–1962 (London: Faber and Faber, 1963), 70, lines 178–79; Rainer Maria Rilke, Duino Elegies, trans. David Young (New York: Norton, 1992), 19, 20.

[34] Ella Ophir, “Modernist Fiction and ‘the Accumulation of Unrecorded Life,’” Modernist Cultures 2, no. 1 (2006): 6–20; Liesl Olson, Modernism and the Ordinary (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009); Lorraine Sim, Virginia Woolf: the Patterns of Ordinary Experience (Farnham, Surrey: Ashgate, 2010).

[35] See Kalaidjian, “The Good Life”; Ardoin, “The Un-happy.”

[36] Jean Rhys, Voyage in the Dark (London: Penguin, 2000), 49.

[37] Jean Rhys, Smile Please: An Unfinished Autobiography (London: André Deutsch, 1979), 19.

[38]For example, in Feeling Backwards, Heather Love resists the “affirmative turn” in queer studies and examines, through an archive of negative feeling, the ways in which happiness and the idea of a “brighter future” are resisted in a range of late nineteenth and early twentieth-century texts about queer desire (Feeling Backward: Loss and the Politics of Queer History [Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2007], 8); see also chapter three of Ahmed’s, The Promise of Happiness, “Unhappy Queers.”

[39] On the feminist politics of failure in Voyage in the Dark, see Anne Cunningham, “‘Get on or Get out’: Failure and Negative Femininity in Jean Rhys’s Voyage in the Dark,” Modern Fiction Studies 59, no. 2 (2013): 373–394.

[40] Kalaidjian, “The Good Life,” 224, 213. Kalaidjian proposes that Sasha’s experience of return as repetition points to a wider “crisis of cultural agency stemming from the traumas of [World War I],” which render Sasha unable to re-access the “good life” upon her return to Paris.

[41] For a discussion of the relationship between happiness and form, specifically narrative, see Soni, Mourning Happiness. While Soni argues that the relationship between happiness and narrative becomes complicated, and corrupted, from the eighteenth century, it seems clear that in the culture at large happiness and the good life have retained their teleological quality, be it in relation to the forms of life that are promised to lead to happiness (marriage, parenthood, success in work), or the structure of other affects to which happiness has become tied in the era of liberal-capitalism (e.g. optimism, hope, effort). See also note 32 on the Classical model and claims to happiness.

[42] See, for example, Kaye Mitchell, “‘They All Know What I Am. I’m a Woman Come in Here to Get Drunk’: Shame, Femininity and the Literature of Intoxication,” European Journal of English Studies 23, no. 3 (2019): 249–62; Patricia Moran, “‘The Feelings Are Always Mine’: Chronic Shame and Humiliated Rage in Jean Rhys’ Fiction,” in Jean Rhys: Twenty-First Century Approaches, ed. Erica L. Johnson and Patricia Moran (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2015), 190–208, and Moran’s many other publications on shame and trauma in Rhys; Erica L. Johnson, “Hontologie: The Chronotope of Shame in Jean Rhys’s Good Morning, Midnight,” Kronoscope 13, no. 1 (2013), 28–46; Cathleen Maslen, Ferocious Things: Jean Rhys and the Politics of Women’s Melancholia (Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2009); Maren Linett, “‘New Words, New Everything’: Fragmentation and Trauma in Jean Rhys,” Twentieth-Century Literature 51, no. 4 (2005): 437–66; Kristin Czarnecki, “‘Yes, It Can Be Sad, the Sun in the Afternoon’: Kristevan Depression in Jean Rhys’s Good Morning, Midnight,” Journal of Modern Literature 32, no. 3 (2009): 63–82.

[43] While there is a significant through line between happiness and spirituality in modernism, that is not a discussion that I have space to pursue here. The modernist epiphany is one example of a category of experience in which happy feelings (joy, ecstasy, contentment etc.) and/or concepts of the good coincide with an intimation of the numinous.

[44] Virginia Woolf, The Diary of Virginia Woolf: 1925–1930, vol. 3, ed. Anne Olivier Bell and Andrew McNeillie (Orlando: Harcourt Brace, 1980), 9.

[45] On the elusiveness and indeterminacy of happiness see McMahon, Happiness, xi.

[46] David L. McMahan argues that recent accounts of mindfulness in contemporary modernity, including Buddhist mindfulness, are “informed by modern literature’s valorization of the details of everyday life, its finely tuned descriptions of the flow of consciousness, and its new reverence for ordinary objects and their capacity to reflect the universal.” The Making of Buddhist Modernism (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009), 218.

[47] Michael Cunningham, The Hours (London: Fourth Estate, 2003); The Hours, dir. Stephen Daldry (2002; Hollywood, CA: Paramount Pictures and Miramax Films,).

[48] I provide a fuller account of Woolf’s engagements with the philosophical idea of happiness and the good in, “Moments of Being, Ethics, and the Good Life,” in The Edinburgh Companion to Virginia Woolf, Modernism and Religion, ed. Jane de Gay and Gabrielle McIntire (Edinburgh University Press, forthcoming 2025).

[49] Stephen Coppel, “Ethel Louise Spowers (1890–1947),” in Australian Dictionary of Biography, (National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, published first in hardcopy in 2022), accessed July 8, 2022.

[50] See, for example, Stephen Coppel, “The Australians Dorrit Black, Ethel Spowers and Eveline Syme,” in Linocuts of the Machine Age: Claude Flight and the Grosvenor School (Aldershot: Scolar Press, 1995), 65–68; Roger Butler, “The Grosvenor School and colour linocuts,” in Printed: Images by Australian Artists 1885–1955 (Canberra: National Gallery of Australia, 2007), 199–205.

[51] On the Grosvenor School and the avant-garde see Phillip Vann, “Pulsating Rhythms: The Radical Achievement of Claude Flight and his Printmaking Pupils,” in Cutting Edge: Modernist British Printmaking, ed. Gordon Samuel (London: Philip Wilson Publishers and Dulwich Picture Gallery, 2019), 38–51.

[52] Lorraine Sim, “The Linocuts of Ethel Spowers: A Vision Apart,” Modernist Cultures 15, no. 3 (2020): 354–76.

[53] Sandra S. Robertson, “Ethel Louise Spowers (1890–1947): Illustrator and Printmaker,” vol. 1 (B.A. Honours thesis, Australian National University, 1985), 69–70. My essay on Spowers is the first publication devoted solely to a study of her art and career, as opposed to brief, collective discussions of “the Australians” affiliated with the Grosvenor School: Dorrit Black, Eveline Syme and Spowers; Sim, “The Linocuts of Ethel Spowers’. For collective discussions of “the Australians” see Coppel, “The Australians,” 65–68; Tracey Lock, “Relaxing the Line: The Linocuts of the Australian Artists Dorrit Black, Eveline Syme and Ethel Spowers,” in Cutting Edge, 68–75.

[54] Biographical details about Monck’s life were obtained from her interview with Val Williams which was conducted in January 1991 when Monck was almost eighty years old; Margaret Monck, interview with Val Williams, January 22 and 23, 1991, “Oral History of British Photography,” Sound Archive, British Library. The interview runs across four cassettes and subsequent references to this interview will be by cassette number (1–4).

[55] Monck, interview, cassette 2, side 1. Wolfgang Suschitzky and his sister Edith were Viennese Jews who emigrated to London in the mid-1930s to escape political persecution. Both Suschitzky and Tudor Hart’s photography reflects their political concerns and sympathies, for example, with working-class poverty, unemployment, welfare and progressive social reform. Like Monck, both photographers worked extensively in London, particularly the East End, in the 1930s and 1940s.

[56] Monck, interview, cassette 2, side 1. She told Williams that the idea of marrying a peer and living at the end of a “big drive” would be like living in a “lunatic asylum,” “not a kind of life that I could accept.”

[57] Unfortunately, the works by Arapoff at the Museum of London are not available for reproduction, but the photograph I’m referring to is clearly staged, and features three extremely dirty (and wide awake) children, two boys and one girl, crammed into a bed in a small, grubby room. The angle at which the photo is taken heightens the sense of claustrophobia. The associated notes and captions by Arapoff clearly express his political views and the intention of the images. In a neat subversion, the young girl is smiling and seems to find the whole performance amusing.

[58] Alan Trachtenberg, “Seeing What You See: Photographs by Helen Levitt,” Raritan Quarterly 31, no. 4 (2012): 4.

[59] Monck comments that the image was self-evident and she didn’t need to push a point. The children, she comments, do not appear dirty or underfed, but look “terribly sad” and she described the image as “horrifying” and “very emotional.”; interview, cassette 2, side 2

[60] Saidiya Hartman, “The Terrible Beauty of the Slum,” Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments: Intimate Histories of Riotous Black Girls, Troublesome Women, and Queer Radicals (London: Serpent’s Tail, 2021), 4–5.

[61] On pessimism see Tyson, “Apocalypse Chic”; for an investigation of “the role of suspicion” as the predominant “mood and method” in literary criticism see Felski, The Limits of Critique, 1.